Slickhorn Canyon Ruins, UT

Fort Ruby, NV

Hobgoblin’s Playground, NV

Far off the beaten path in southern Nevada’s Clark County lies an ancient treasure surprisingly few know about: Little Finland, also called the Hobgoblin’s Playground. Dragons and other mythic beasts of yore seem to have turned to stone here, reminding us of times long gone by. Witness these beautiful sandstone formations turn red, orange and golden in the fading sunlight.Like the Valley of Fire, only 30 km away as the crow flies, Little Finland features red sandstone formations that were formed by shifting sand dunes millions of years ago when dinosaurs still roamed the earth. So comparing these formations with prehistoric beasts is actually not that far-fetched.The dunes were formed by a process known as Aeolian erosion, named after the Greek god of wind, Aeolus. Wind, though less powerful than water, unleashes its full force in vast, arid regions and can erode, transport and deposit materials. Over time, the sand cements into rock and is further shaped by the wind, leaving us with the incredible formations at Little Finland that we see today.Though most visitors try to reach Little Finland an hour before sunset to play with the hobgoblins while basked in the red light of the fading sun, those who can stomach the soaring temperatures and sun will get some beautiful shots as well.Pros arrive at sunset to witness the way the sun’s rays turn the sandstone formations into a sea of red, orange and yellow and then camp out in their cars or a tent to sleep under the vast sky and stars. Getting up at the crack of dawn will pay off for watching the sun rise behind the fairytale giants.Getting to this magical place is unfortunately a little more difficult than using fairy dust. Visitors really need an all-terrain vehicle and a tendency for roughing it if they want to enjoy this natural miracle. Unlike the Valley of Fire, Little Finland is not a state park and therefore the facilities usually associated with one are not available.

Here’s how you’d get to Little Finland: About five miles from Mesquite, take I-15 exit 112 towards Riverside/Bunkerville (about 1 hr from Las Vegas). Follow directions for Gold Butte Backcountry Byway and take a right onto it. This paved road turns into a dirt road after a few miles.Follow signs for “Devil’s Throat” – a sinkhole. Where the road forks, take the right branch and follow it until it turns into Mud Wash, the river bed you will drive on. Follow it for a few miles and take the right branch again where it forks. This should lead you to Little Finland. A word of caution to those planning a first visit: The sandstone formations at Little Finland are very fragile, so tread carefully or they may be lost forever. Little Finland’s inaccessibility is what’s saved it so far and it’s probably just as well that it is missing from most maps and travel guides.

Shauntie Ghost Town, UT

Shauntie was a boom town during the years 1872 to 1877 . There were over 40 houses of various types, several businesses including a hotel, several saloons, a post office, two stores and a smelter. When the mines gave out so did the town.

Shauntie was a mining town west of Milford flat, based in the foothills. The town burned down twice and when the mine was abandoned and people moved..

Early in 1870 prospectors, drifting east from the boom at Pioche, Nevada, and west from the spectacular strike at the Lincoln mine in the Mineral mountains near Minersville, found silver in paying quantities in the Picachio mountains across the valley from Minersville to the west. On July 8, 1870 the Star district was organized. The silver strikes attracted much excitement in both Utah, and Eastern Nevada. By early 1871 the area was so flooded with prospectors, and so many claims were being filed that the district was divided on Nov. 11, 1871 into two districts, the North Star, and the South Star. By 1880 over 1,600 claims had been staked; and the low mountains were swarming with prospectors and mining men. The mines were grouped in five or six different areas, or canyons, each with it’s own mining camp: North Camp or Shenandoah City to the North, Foothills to the East, South Camp to the South, Elephant City or Middle Camp in the middle of the range, and West Camp and Shauntie on the West side of the Mountains.

Because it was located at the only regularly running water in the area, Shauntie became the smelting center for the two districts. In 1873 the Shauntie smelter was built with two stacks. In 1874, this smelter was torn down and the larger Shumar Smelter was built, with one stack, but having a 20 ton per day capacity; and employing as many as a hundred workers hauling and smelting the ore being brought in from the Rebel, Elephant, Miner’s Dream, Burning Moscow, and other mines. During the years 1872 to 1877 Shauntie boomed. Soon Shauntie was vying with Shenandoah City as the leading town in the area. Shauntie had over 40 houses of various types, and several businesses including a hotel, several saloons, it’s own post office, and stores. In June of 1875 the smelter burned to the ground, but it was quickly rebuilt and pouring out even more bullion than before. In 1876 Shauntie, itself was destroyed by fire. This still didn’t stop Shauntie. The town was soon rebuilt and was attracting the attention of mining men from all over the west. The veins in the Star districts proved to be shallow however, and by 1877 many of them were closing as their veins pinched out. Just as depression set in and the miners and prospectors of Shauntie were wondering where to go next, News of new discovery excited the ears of the investors and miners. A fabulous new mine, the “Bonanza” had been discovered just 10 miles to the Northwest in the San Francisco Mountains. As fast as the camps of the Star districts were built, so they were abandoned. As news of the discovery reached the others in the district, they just picked up and left, flocking to the new mine which had just been re-named the “Horn Silver” hoping to find work, or profit at the new diggings. Shauntie and the other camps were left abandoned for thirty three years. In 1910 there was a small resurgence when the Burning Moscow, Cedar-Talisman, and Harrington-Hickory mines were re-opened to mine out the low grade ore that was left behind during the boom period. Shauntie again was the center of activity. The Post Office was changed to Moscow in honor of the Burning Moscow mine, then to Talisman, but the locals still just called it Shauntie. By 1920 the low grade ore was mined out, the few people that stayed to carry on small time mining moved to Milford leaving Shauntie and the other Star District camps deserted and crumbling. Over the years the townspeople and farmers around Milford dismantled and hauled off everything they could use from around the mines leaving just a few shacks and head frames at the mines. Foundations and broken glass scattered through the sagebrush and junipers area all that is left of what was once the thriving camp of Shauntie.

South Camp 1800s Mining Ruins, UT

South Camp 1800s Mining Ruins – The remains of these rock cabins are some of the last vestiges of “South Camp”, one of the leading mining camps in the Star Range, which was active in the late 1800s. More than a hundred years ago this was a bustling town. With an active stagecoach line from Milford which led west through South Camp to Nevada. Homes, stores, and saloons once stood here. The mines in the area are are open yet dangerous, although some of them still hold priceless ore for those who are up for the adventure.

Location For Google Map Click Here

Locating Fossilized trilobites In Nevada

located in the Pioche Hills located in eastern Lincoln County, Nevada near the historic mining town of Pioche is a formation known which creates The Lower-Middle Cambrian boundary interval within the southern Great Basin and Mojave Desert region. Here in the long outcrop a belt occurs within a mountain chain which trends southward along the west side of the Bristol, Highland, Chief, and Burnt Springs Ranges to Lime Mountain in the Delamar Mountains. With in the shale of these ranges especially the Middle Cambrian Pioche Shale occurs which in the Pioche Hills located in eastern Lincoln County, Nevada. These areas are rich in fossilized trilobites within the prehistoric Cambrian shelf a transect would associated with depth changes across the shelf a prehistoric ocean.

Locating Fossils

The most efficient way to locate fossilized trilobites is to examine the shale formations both above and below the surface is to dig into the slabby-weathering siliceous shales, exposing fresh sedimentary strata below the surface. Fortunately, most of the shales within a few inches of the surface are severely fractured; hence, little splitting of them is necessary, since they tend to separate from the outcrops in thin sheet-like plates. Watch for the fossil compressions and impressions along the bedding planes of every shale fragment you remove from the hillside exposures. The deeper you dig, though, the more thickly bedded the opaline shales become, until at last it will become necessary to begin splitting the extremely dense, concrete-like rocks. When doing this, always remember to wear safety goggles, or at least some kind of eye protection such as sunglasses. The denser, thick-bedded opaline strata crack apart only with the greatest of applied brute force, thus increasing the likelihood that sharp fragments might launch off the matrix into your eyes. Stand slabs of shale on end, then give them a sure whack with the blunt end of a geology hammer. If you’re fortunate, the sedimentary layers will break apart along their original planes of deposition, revealing perfect carbonized leaf and seed impressions and compressions to their first light of day in approximately 16 million years.

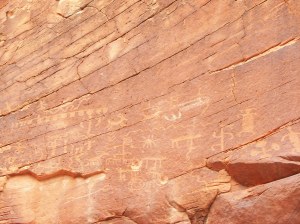

Nampaweap Petroglyphs, AZ

Strawberry Point. UT

Strawberry Point Drive out to the scenic view point of Strawberry Point for spectacular views of forested land and red rock formations. A high clearance vehicle makes this a nicer drive. Duck Pond is 9 miles from the turnoff to Strawberry Point. Strawberry Point is a mountain cliff in Iron County in the state of Utah (UT). Strawberry Point climbs to 8,373 feet (2,552.09 meters) above sea level. Strawberry Point is located at latitude – longitude coordinates (also called lat – long coordinates or GPS coordinates) of N 37.751088 and W -112.943001.

Anyone attempting to climb Strawberry Point and reach the summit should look for detailed information on the Strawberry Point area in the topographic map (topo map) and the Summit USGS quad. To hike and explore the Utah outdoors near Strawberry Point, check the list of nearby trails.

Read Condition Reports | Add Condition ReportView Locator Map and Local WeatherPeak Type: CliffLatitude: 37.751088Longitue: -112.943001Peak Elevation: 8,373 feet (2,552.09 m)Nearest City: Summit (3.2 miles away)

Power Line Road Petroglyphs, NV

Image Pending

Coordinates for the Power Line Road:

| Description | Lat/Lon NAD 83/84 |

| Las Vegas Blvd & Power Line | 35d 56.285′ 115d 11.151′ |

| Magnolia Sub Station | 35d 55.697′ 115d 10.495 |

|

Right turn after power pole #2068 |

35d 55.455′ 115d 07.462′ |

| Turn right into the wash | 35d 54.966′ 115d 07.379′ |

| Parking area | 35d 54.541′ 115d 07.459′ |

| Last dry falls/main site | 35d 53.848′ 115d 07.390′ |

The Moon, AZ – GrandStaircase Escalante National Monument

The Moon - GrandStaircase Escalante National Monument

The Moon - GrandStaircase Escalante National Monument